Orhan Pamuk paid two-day visit to Tbilisi

On Mar. 12, recipient of the Nobel Prize, Turk writer Orhan Pamuk arrived in Tbilisi where he will have two meetings during his two-day visit. The first meeting will be held with students of Free University on Mar. 12, followed by Pamuk’s second meeting with readers at Rustaveli Theater on Mar. 13 at 19:00.

Orhan Pamuk is a Turk writer and first Turk writer to receive a Nobel Prize in literature. Pamuk became widely popular after receiving the Nobel Prize for being one of the few Turks who spoke out about the Armenian Genocide of 1915-23 in Turkey.

It all started in February 2005 when Pamuk gave an interview to the Swiss Das Magazin Weekly in which he declared that “30,000 Kurds and 1,000,000 Armenians have been killed in Turkey”.

“But almost nobody dares to speak out about it. So, I have to say it,” Pamuk had added.

Turkey, which leads an active struggle against the international recognition of the Armenian Genocide of 1915-23, burst into outrage and started persecuting Pamuk, and the latter was compelled to leave the country and live in England for a while. Later, he returned to his country where he publicly explained what he had meant during an interview with BBC. Pamuk said he simply wanted to defend freedom of speech, which is the only way for Turkey to come to grips with its past. “The issue of the fate of the Ottoman Armenians is a taboo in our country, but we have to speak out about it,” he declared during that interview.

In the fall of 2005, the Turkish authorities introduced the special Article N 301 “On Offense to the Turkish People”, according to which they brought up a charge against Pamuk. The Turkish court imposed a 3,850 dollar fine on Orhan Pamuk for his statement on the genocide of the Kurds and the Armenians.

The president of the Turkish Fund for Economic and Social Sciences called Pamuk’s condemnation an “embarrassment for Turkey that goes back to the origins”. “People have a right to express their opinions. That can’t be a crime, if the opinion hasn’t been expressed to instill hatred in the society and make the people act violent. Pamuk spoke as an author. I think the court ruling is totally wrong,” the president said.

The writer’s sentencing for his position on the Armenian Genocide sparked great reactions around the world. The European Union urged Turkey to annul Article 301 “On Offense to the Turkish Nation”, but it wasn’t able to force Turkey to do that.

In 2006, the writer received a Nobel Prize in literature. “He found new symbols of the clash and combination of cultures in his search for the melancholic spirit of his hometown,” these were the words stated by the members of the committee that granted Pamuk the Nobel Prize, but it was clear that the events of the previous year (2005) also played a great role in the selection.

Orhan Pamuk has addressed Turkey’s persecution against non-Turkic peoples several times. The following are some excerpts from his book “Istanbul: City of Memories”.

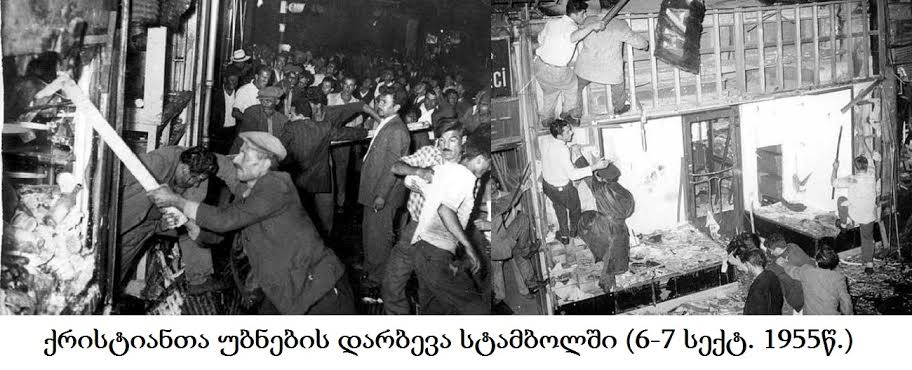

“…Horrible events on 6-7 September 1955. The agent for the Turkish special service threw a bomb in the house in Thessaloniki where Ataturk was born. After Istanbul’s newspapers spread the news across the city in a special edition (with numerous copies), aggressive Turks gathered at Taksim Square. In the beginning, the protesters raged the stores of Beyoglu where I would go with my mother, and then they continued to rob and burn everything in Istanbul until morning.

The most horrible events were taking place in the parts of the city where there were many Greeks, including Ortakyoy, Balikli, Samatie and Fenere…The protesters destroyed and burned dairy and grocery stores, invaded homes and raped Greek and Armenian women. It is safe to say that their violent acts were similar to those of the person who robbed Mehmed Bnakal after the seizure of Istanbul. They terrorized the city and turned it into a real hell where the disturbances were more than what all Christian Europeans knew about the brutalities of the East. The terror continued for two days. Later, it became clear that the organizers, that is, the encouraging authorities, were telling the protesters that they wouldn’t be punished for their actions.

In the morning, the cities of Istiklyal and Beyoglu were filled with products that the robbers hadn’t managed to take from the destroyed stores, but had destroyed the stores with pleasure and had left them in ruins. There were all types of scraps and colors, carpets, clothes, refrigerators that were just being imported in Turkey, radios, laundry machines, broken porcelain silverware and torn toys (at the time, the best toys were sold in Beyoglu), kitchenware, technological appliances, pieces of lamps and the aquariums of the time. There were broken bikes, cars that had been spun or burnt, broken pianos and mannequins that were taken off display and wrapped in clothes and with broken hands and looking toward the sky with a look of indifference. The tanks that had arrived late were parked to regulate the disturbances.” (“Istanbul: City of Memories”, O. Pamuk).

“…During the years of my childhood and teenage years, Istanbul was no longer looking like a cosmopolitan city. Gotye (and not only him) stated that one could hear Turkish, Greek, Armenian, Italian, French and English words spoken on the streets of the city 100 years before I was born. Knowing that the people living in that Babylonian hell spoke in several languages fluently, Gotye, as a true Frenchman who only knew his native language, felt a little ashamed. After the establishment of the republic, the Government’s attempts to make Istanbul Turkified (those attempts could be referred to as the end of the seizure of Constantinople or an ethnic cleansing in its own kind) contributed to the elimination of those languages. I remember, during my childhood, if anyone spoke in Greek or Armenian (the Kurds preferred not to speak in their native language amongst people), the others would start whistling “Citizens, speak in Turkish”! Those words were posted on different signs everywhere”. (“Istanbul: City of Memories”, O. Pamuk).

“…Empty apartments, homes that were robbed from Greeks, Armenians and Assyrians who were saved from persecution and that were “challenging the future”, had tilted a little (some were leaning on each other, looking like a satirical picture), deformed roofs, boxes, window frames-all this wasn’t right and beautiful at all for the people because they showed poverty, despair and abandonment. Only a person from abroad who visited this poor district could admire the accidental beauty of the deserted area in the picture” (“Istanbul: City of Memories”, O. Pamuk).

Արևելահայերեն

Արևելահայերեն Արևմտահայերեն

Արևմտահայերեն Русский

Русский