A small country but a big nation: how genocide shaped the Armenia of today

“The guardian’s” Article about Armenian Genocide

As Armenians mark the beginning of violence that left 1.5 million dead, Turkey’s lack of contrition leaves descendants struggling to reconcile loss and renewal.

In the beginning you hardly notice them: little lapel buttons in purple, yellow and black to mourn the dead and a lost homeland. But then there are the posters, T-shirts, umbrellas, bumper stickers, even cakes, all bearing the same forget-me-not flower designed to commemorate the tragedy of a nation.

It is the symbol of the centenary of the Armenian genocide of 1915, being marked this week in solemn ceremonies in Yerevan and wherever in the world this ancient people fled in the wake of the mass atrocities suffered in the dying days of the Ottoman empire.

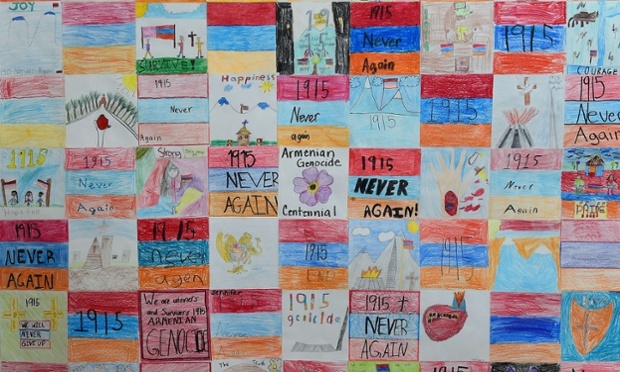

This newly invented tradition, a poppy-like throwback to the killing fields of eastern Anatolia, has triggered complaints about commercialisation. But it has caught on. Across Armenia, in schools and homes, and as far away as the diaspora community of Glendale, California, children have picked up crayons and scissors to make their own paper flowers or have planted the real thing in remembrance of the horrors that beset their forebears.

Final preparations for Friday’s commemoration are under way at Armenia’s genocide memorial on the Tsitsernakaberd plateau, overlooking Yerevan. It features a bunker-like museum and a tapering grey stele pointing skywards like an accusing finger. To the south, on the Turkish side of the long-closed border, Mount Ararat beckons through spring clouds, snow-covered and majestic.

The big names on the day will include Vladimir Putin and François Hollande, leaders of the largest of the 20 countries to have formally recognised the genocide. But western governments that have not, including Britain, are sending low-profile officials to Yerevan, and far more senior representatives to Turkey to mark the centenary of the Gallipoli landings, the date deliberately and cynically chosen by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – so furious Armenians believe – in order to sabotage their own ceremony.

The slogan lies at the heart of the campaign for the Turkish state to recognise that its Ottoman predecessor annihilated up to 1.5 million Armenian citizens, starting on 24 April 1915 with the arrest of intellectuals in Constantinople and continuing with a centralised programme of deportations, murder, pillage and rape until 1922. The shadowy Teskilat e-Mahsusa (“special organisation”) drew up plans and sent coded, euphemistic telegrams to provincial officials and dispatched its victims on railway journeys to oblivion in the deserts of Iraq and Syria. Henry Morgenthau, the US ambassador, described the Turks as giving “a death warrant to a whole race”.

On 23 April, at Etchmiadzin, seat of the Armenian Apostolic church, the martyrs will be canonised collectively – renewing a tradition dating back 1,700 years. “We have to liberate our own people from hostility and hatred,” explained Bishop Bagrat Galstanyan. “And we have to liberate the Turks, to cleanse themselves from the pain of genocide.”

It was at Etchmiadzin in 1965 – the 50th anniversary of the slaughter, a key moment of Armenian national awakening, and when many witnesses were still alive – that the bleached bones of the dead were brought from Deir ez-Zor in Syria for reburial.

Numerous centenary events, such as conferences, exhibitions and concerts, underline how closely this country’s identity and future are bound up with the bloody past. Raw emotion, competing narratives and an ongoing diplomatic crisis make for a difficult combination.

“International recognition is fine but, if Turkey doesn’t do it, then we won’t have the security we need,” said Tevan Poghosyan, an MP for the nationalist Heritage party. “It is a security issue because the genocide happened to us. It is our nation that lost its homeland and was scattered around the world. It is not just a historical issue.”

Armenian government policy does not include demands for territory or reparations, as organisations in the more militantly nationalist diaspora would like. Yerevan seeks normalisation of relations with Ankara, starting with the crucial reopening of the border, to promote reconciliation that it hopes will eventually bring genocide recognition – even if that takes decades.

Optimism peaked in 2009, when protocols brokered by the Swiss and endorsed by the US and EU were signed in Zurich, crucially with no mention of the horrors of 1915. But they were never ratified – because the Turks insisted on linking them to progress on Nagorno-Karabakh. It has been downhill ever since, relations now frozen in an atmosphere of deep mistrust. The vacuum is being filled by strident, anti-Turkish voices from the diaspora, and attitudes are hardening at home as well.

Talk of greater unity is rife. “We live in a small territory but we are a big nation,” said Hranush Hakobyan, minister for the diaspora. “Anyone who deals with us is dealing with 12 million Armenians.” The country’s entry to this year’s Eurovision song contest will be sung by a six-strong band – one singer each from the five continents of the diaspora and one from the republic. The title of the song is Don’t Deny.

Read the full article here.

Արևելահայերեն

Արևելահայերեն Արևմտահայերեն

Արևմտահայերեն Русский

Русский